A Breath of Fresh Air: The Importance of Nasal Breathing

by Mitchell Thompson

(8 Minute Read)

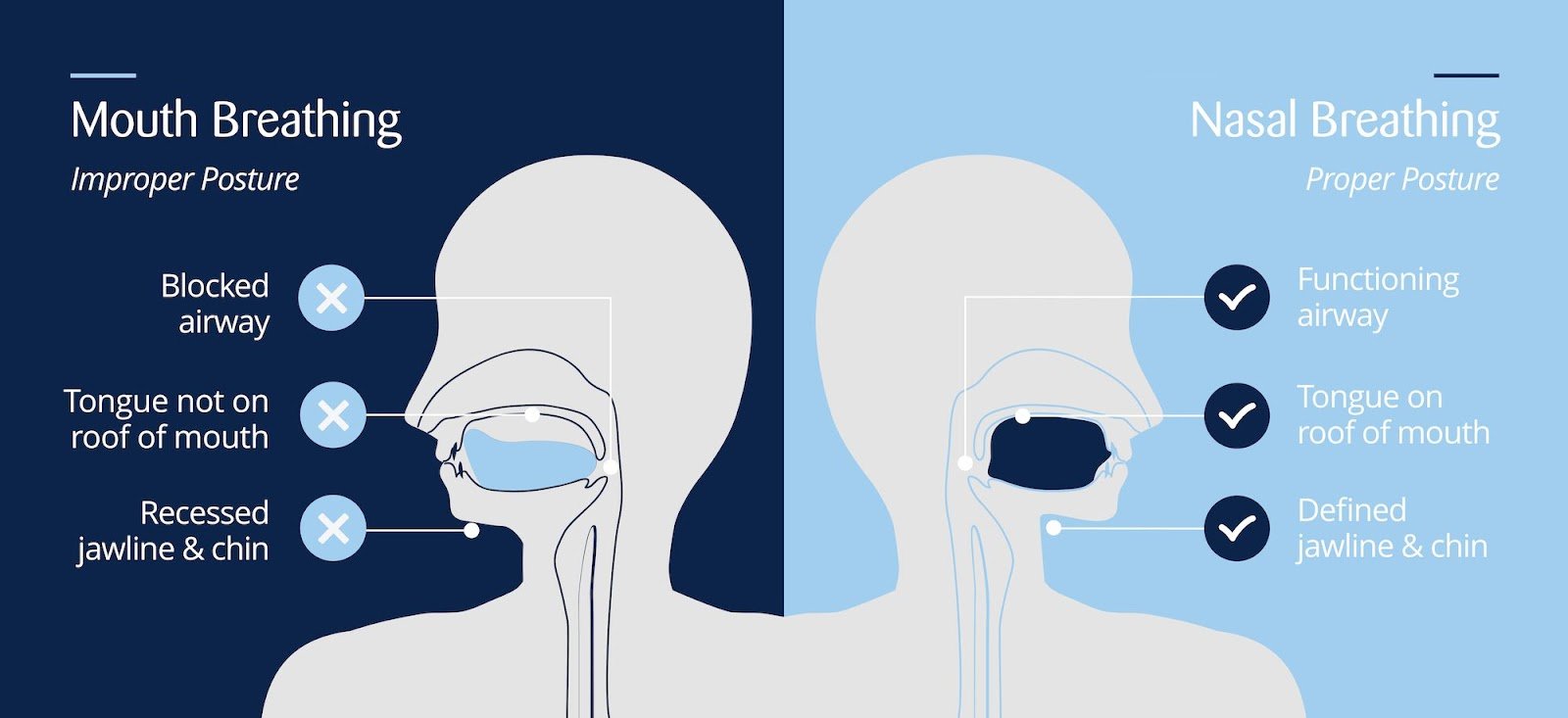

If you’re anything like me, then you probably never thought about whether or not it made a difference if you’re breathing through your mouth or breathing through your nose. We, as human beings, breathe on average 25,000 times per day. That is roughly 14-18 breaths per minute. Most people breathe through their nose, however more and more are shifting to a habit of mouth breathing. Believe it or not, there is a huge difference between breathing through your nose versus breathing through your mouth. To such a degree that physical deformations in developing children and adults (such as the narrowing of airways that lead to obstructive sleep apnea, receding mandible/lower jaw, narrowed maxilla/upper jaw, and many more) are produced as a result of chronic mouth breathing. When you breathe through your mouth, you are misplacing your tongue’s naturally designed resting position from the roof of your mouth to the floor of your mouth. Also, when you breathe through your mouth, you are inhaling “dirty” unfiltered atmospheric air, compared to breathing through your nose where you’re inhaling “cleaner” air as the “dirty” atmospheric air is then filtered through your nose. This article will not only explain the significant of nasal breathing over mouth breathing, but it could potentially save you, your children, or the people you care about from unnecessary pain and suffering.

Facial/Cranial Deformities

First thing’s first, it’s important to understand that mouth breathing does have its place in our lives. If we need to recruit a lot of air in a short amount of time, breathing through the mouth is very beneficial. If we need to exert a maximal output of energy, breathing through the mouth - especially upon exhalation - can be very beneficial and sometimes preferred. The intentional use of oral exhalation is actually one of the most effective methods for offloading the carbon dioxide in our body.

So mouth breathing has its place. We just need to know its role.

There is a biological blueprint that the human species follows no different than the bioevolutionary blueprint of all animals. Fish have gills that help them breathe underwater, and all fish maintain the basic anatomical structure required to facilitate such underwater breathing. Now, that is not to say that every fish’s anatomical structure is exactly the same, nor that some fish’s anatomical structure have more of a genetic predisposition to genetic deformations. This is simply to say the the structure of all fish gills follow a specific bioevolutionary model. For humans, the bioevolutionary model for our breathing habits are based in nasal breathing over oral breathing and it’s evidenced in subtleties like the evolutionarily designed placement of our tongue - however it is most evident in the adverse affects of long-term/chronic mouth breathing.

Without boring you with the orthodontic science, it has been shown that the natural position of our tongue in our mouth plays a vital role in how our face and skull develop. Through the 1960s-1980s, a dentist named Dr. Egil Harvold noticed an observable correlation between his patients crooked teeth and their shared mouth breathing habits. Most, if not all, of these patients seeking orthodontic treatment were habitual mouth breathers and maintained an underdeveloped/obstructed nasal breathing pathway. To test his hypothesis, Dr. Egil Harvold conducted a series of experiments on monkeys to determine the developmental implications of chronic mouth breathing over nasal breathing. To do so, he plugged the nose of test monkeys at an early age to force them to breathe through their mouth and compared their developmental progress to a set of control monkeys (who naturally breathed through their nose, like humans). His findings showed that the monkeys who depended on oral respiration (mouth breathing) developed crooked teeth, a receding mandible (lower jaw), and a narrowed maxilla (upper jaw). Due to these initial findings, it has become universally accepted that the affects of mouth breathing can cause a change in the posture of the tongue, which can have a downstream affect of producing severe facial/cranial malformations in the development of any child.

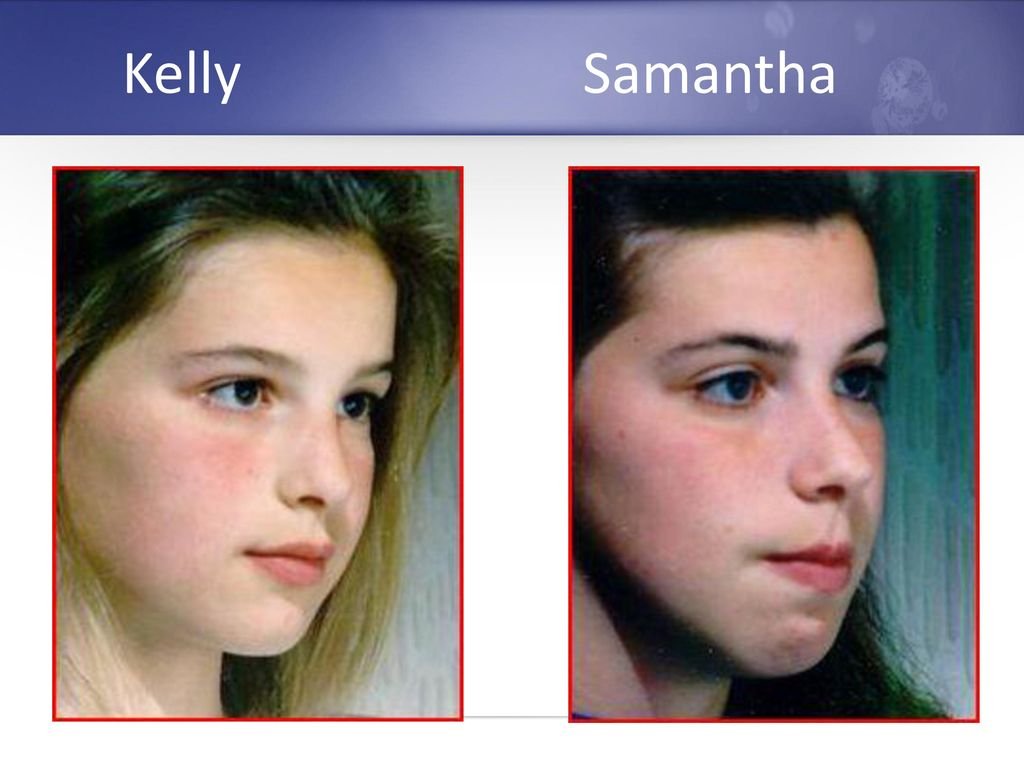

Another renowned orthodontist named Dr. John Mew substantiated the findings of Dr. Egil Harvold through his own work with his own patients. In the pictures below, you will notice two young sisters, Kelly and Sam, who came to Dr. Mew to correct their crooked teeth. In treating them, one of his immediate methods to both was to start breathing through their nose (as they, like most patients seeking orthodontics, were chronic mouth breathers). Over the course of several years, Kelly followed through with Dr. Mew’s nasal breathing advice and Sam did not.

Kelly, age 7 (left) and Sam, age 8 (right). Both are nearly identical in their facial development.

Kelly (left) and Sam (right) several years later. Kelly followed Dr. Mew’s nasal breathing advice - Sam did not.

As you can see, there is a drastic difference in the overall facial/cranial development between the sisters. The same developmental deformities that Dr. Egil Harvold found in his monkey experiments were found in the sisters, as will be commonly found in most chronic mouth breathers if corrective changes aren’t made. Sam, unlike Kelly, maintained more of her crooked teeth, developed a receding lower jaw, and developed a more narrow upper jaw.

All from breathing differently.

How crazy is it to think that breathing through your mouth versus breathing through your nose could have such drastic implications on your development as a human? What’s even crazier is the recency in which this information has come into our conscious awareness. Thank goodness we are more knowledgable today so that we can mitigate the unnecessary suffering of tomorrow.

How Respiration (Breathing) Works

We take breathing for granted instead of taking advantage of its function. When we breathe through our nose, we are adhering to our body’s natural anatomy. Our body is designed to inhale oxygen and “clean it” through our nose before it reaches our lungs, whereas the inhaling of oxygen through our mouths directly exposes our lungs to the unfiltered/uncleaned atmospheric air.

Again, without snoozing you with an entire lecture on respiratory science, there are some fundamental concepts that must be understood. For instance, it is important to have a basic understanding of how breathing even works (whether through the mouth or through the nose). But to keep things simple:

Oxygen = Good (fuel)

Carbon Dioxide = Bad (waste)

Our bodies use oxygen to fuel its system, while producing carbon dioxide as the reciprocal waste of such fuel. Carbon dioxide is a gas produced in the body when we burn food for energy, and the “fumes” of carbon dioxide are carried from the muscles/tissues/organs to the blood and eventually from the blood to the lungs. This inverse process happens simultaneously as oxygen is carried to the lungs, diffused into the blood, and carried to the muscles/tissues/organs.

When we breathe, oxygen is inhaled in, reaches the lungs, and is diffused into the blood. As this happens, the carbon dioxide in our blood (that has reached the lungs) is diffused into the lungs and inversely exhaled out. This process is known as “gas exchange” and is fundamental for all living creatures. Meaning all animals, in some form, utilize this process of gas exchange.

To be a little more specific, every time we inhale, oxygen enters the trachea, passes through the bronchi (meaning branch) and eventually reaches the alveoli (air sacs at the end of bronchioles/individual ‘branches’). These air sacs are the location in which gas exchange occurs.

Visual model depicting what gas exchange in alveoli looks like.

But before this gas exchange can occur, the oxygen within the air we breathe must be conditioned before it can be diffused into the lungs and eventually into our bloodstream. This means that the oxygen from the air must be pressurized and humidified in some way before it will be diffused into our bloodstream. The red blood cells in our lungs can only extract/pick up conditioned oxygen (that has been pressurized and humidified). Our lungs themselves will condition oxygen (whether inhaled through the nose or mouth) and is the finalizer of what oxygen is able to be diffused into our blood. That is to say that our lungs act the primary conditioner for the oxygen we absorb into our body. Though the lungs are the primary conditioner, the filtration system of the nose also acts to condition oxygen before it even reaches the lungs.

With respect to the nose, the nose should be seen as an air filtration system with many different structures within it that help cleanse the air before it reaches the lungs. The nose has hair and cilia to trap dirt and particles, sinuses to produce mucus to keep the nose moist, and turbinates (or conchae) to pressurize and humidify (condition) the oxygen of the inhaled air.

Why is this important?

Because the oxygen within the air we breathe, as previously mentioned, must be conditioned before it can be diffused into the lungs and eventually into our bloodstream. Remember, the red blood cells in our lungs can only extract/pick up conditioned oxygen. When we breathe through our nose, the filtering process conditions the atmospheric air to where it is diffusible before it even reaches the lungs. It is in thanks to this natural process where up to 20% more oxygen is produced per nasal breath versus a single mouth breath.

This is why nasal breathing is so important. Our bodies were literally designed to breathe through our noses. We haven’t even talked about nasal/mouth breathing when it comes to athletic performance, where utilizing difference modes of breathing can be very effective - such as the offloading of carbon dioxide through the mouth or sometimes recruiting a lot of air at once via oral respiration. This article is less about nasal breathing over mouth breathing in regards to athletic performance and more about the first principles of nasal breathing all together.

Becoming More Mindful

It is universally accepted that we spend about 1/3 of our lives sleeping. Where mouth breathing really affects people is when they are not able to be consciously mindful of their poor mouth breathing habit. There are many different methods to help correct this bad habit, such as wearing restrictive mouth guards or taping the mouth slightly at night (both act in limiting how much the mouth can open and emphasize a dependence towards nasal breathing). Though I do not prescribe or advise these methods, at least initially, I recommend that everyone develop a better nasal breathing habit while they’re consciously awake so that the nasal breathing habit can translate better when unconsciously asleep. Better than this would be to hyperfocus on nasal breathing while exercising and to eventually have entire workout sessions be nasal breathing only. Though sleep-aid tools exist (even at-home remedies like taping your mouth closed) and their potential benefits are substantiated, I would recommend that we all become more mindful of breathing through our noses more intentionally while we are consciously awake so that, over time, our unconscious chronic sleeping habits can be remedied.

An example of “mouth taping” to limit how much the mouth can open while sleeping.

No different than the concept of learning about our poor posture and subsequently making the corrective changes, the idea of utilizing nose breathing more intentionally in our day-to-day lives is only beneficial (especially in the long run). Not only will it benefit you, but it could potentially save someone you love from developing or exacerbating chronic biological malformations. The implications of breathing through your mouth versus breathing through your nose is substantial. There is the potential for developmental deformities, as well as a potential loss of 20% of conditioned oxygen per breath. The developmental deformities themselves cause many downstream problems, such as a narrowed nasal airway leading to obstructive sleep apnea, receding lower jaw, and the narrowing of the upper jaw. The effects of mouth breathing are correlated to sleep apnea, chronic allergies, frequency of colds/sinus infections, respiratory issues like asthma, and much more. However the loss of potential oxygen per breath is even more telling. This loss of 20% of oxygen per breath, over the span of 25,000 breaths daily, in accumulation will surely cause an overall decrease in lung function. This decrease in lung function, coupled with lack of exercise and other potential harmful habits like smoking, should be the most jarring variable when considering how you will inhale your next breath.

Most mouth breathers are unaware of the seriousness of the bad habit. I, myself, still catch myself mouth breathing from time to time and that’s okay. Whenever I catch myself, I am able to go longer and longer periods of not breathing through my mouth because the mindful behavior of intentional nasal breathing is becoming more and more habitual. Once a better behavior becomes habitual enough, its newfound strength allows us to move on from the old behaviors without looking back.

In conclusion, you should always be intentionally breathing through your nose unless you are exercising or are needing to recruit a lot of oxygen and subsequently offload a lot of carbon dioxide. So long we are mindful of when we are mouth breathing versus when we should be nose breathing, we can take advantage of our bodies natural anatomy and not take something as simple as breathing for granted.